Introducing three T-CiRA researchers working on the clinical application of iPS cell technology

Teruyoshi Yamashita

Striving to find cell therapy treatment options for intestinal diseases with a spirit of curiosity and determination

All vertebrates have what are called "neural crest cells," which play an important role in growth and development. Because neural crest cells have the ability to migrate to different locations of the body and change from one cell type to another (also known as differentiation), their use in cell transplantation therapy holds a lot of promise. I am a member of a team working on the Neural Crest Cell Project 1 at T-CiRA, where we are using this technology to create neural crest cells from iPS cells, a technique that was established by our researcher. Our goal is to use these to produce enteric neurons, nerve cells which make up the nervous system of the gastrointestinal tract, in order to develop new drugs for cell therapy treatment for people with congenital intestinal diseases.

1 Basic platform and application research toward drug discovery and regenerative medicine using human iPS-derived neural crest cells.

Teruyoshi Yamashita

Having applied for the research center in-house project TEC, for which researchers propose their own themes and can obtain a budget to carry out the research, Teruyoshi succeeded in inducing differentiation of neural crest cells, based on research findings by CiRA's Dr. Makoto Ikeya. Currently, as part of the Neural Crest Cell project in T-CiRA, he is working on the development of iPS-cell derived neural crest cells in order to develop a new form of cell therapy treatment.

Yoshiaki Kassai

A front-runner leading the way in immunotherapy

The single defining characteristic of T-CiRA as a workplace would probably be expressed best with the word "diversity." We are conducting joint research with professors from Kyoto University in a format we call in Japanese "eating from the same pot of rice." And new science requires a wide range of expertise, so Takeda's research team is itself made up of members with many different career backgrounds. We also work closely with the Boston research team in order to expand our global reach. While learning about leadership and how to work in such a diverse environment, I think that I have grown a lot, not only as a researcher but also as a person.

"When you feel lost, just move forward."

Yoshiaki Kassai

Yoshiaki is a Takeda research team leader working together with Dr. Shin Kaneko of CiRA to develop new immunotherapy using iPS cell-derived T cells. Currently, he is focusing on iPS cell-derived CAR T-cell therapy for blood cancer patients, with the aim of holding clinical trials in the near future.

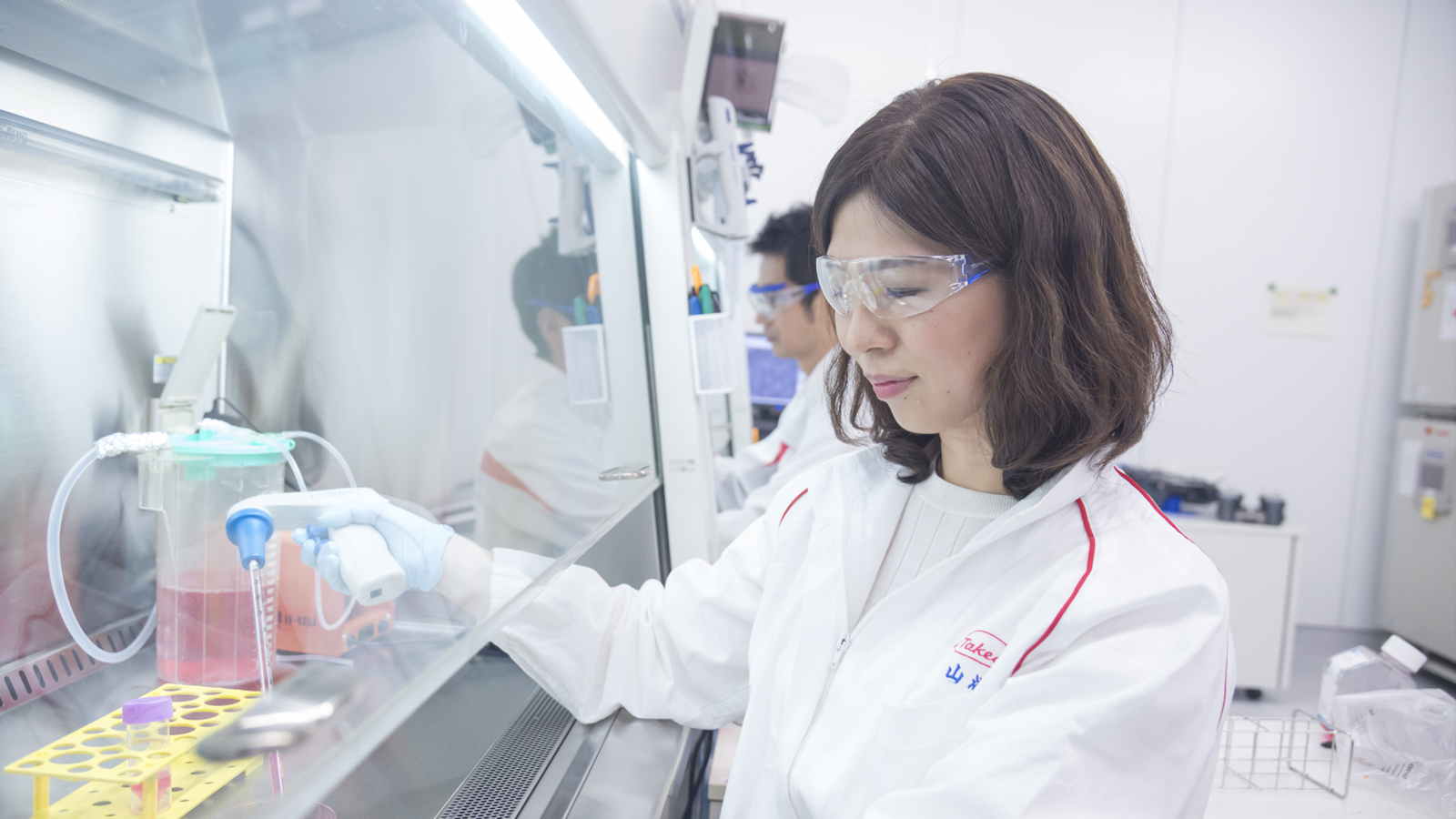

Noriko Yamazoe

Determination and flexibility are keys to success

I am working to create iPS-cell-derived beta cells, the cells found in the pancreas that secrete insulin, with the aim of developing a new practical treatment for type I diabetes. The key to this research is replicating the environment created over several months in the human womb in a test tube. However, the combinations of conditions and factors are limitless, so if the condition of the original cells varies even slightly, the quality of the cells we produce will be different even if the same process is carried out. For this reason, we repeatedly run a trial-and-error process in order to find a stable method to produce cells of a consistent quality among the tens of thousands of conditions. It takes a month to test just one condition, and any promising methods that show potential require a 6-month efficacy evaluation test. So, the satisfaction of seeing positive results is all the greater.

At home, I have two sons, now aged five and eight, and they keep me very busy every day. Thanks to our flexible work-from-home systems, I can use my time efficiently and take on big projects while also spending time with my children.

"Where there’s a will, there's a way."

Noriko Yamazoe

Since joining the company, Noriko has participated in research into creating pancreatic beta cells from iPS cells. In Pancreatic Beta Cell Therapy Project 2 she has continued her work as a core researcher of pancreatic beta cells and has succeeded in producing iPS cell-derived islet-like cells (iPSC). The aim is to enable the clinical application of these in combination with medical devices.

2 Research on cell therapy for type 1 diabetes.